![]()

0️⃣ Foundation – where does “termination” actually live?

Before you argue about wrongful termination, you first need to know where termination actually lives inside the FIDIC Yellow Book – and how those clauses connect to performance security, payment, and the claims system.

In the 📒 2017 Yellow Book, termination doesn’t sit in a single clause you can quote in isolation. It’s a cluster of provisions that talk to each other:

- Clause 1.16 – Contract Termination: the gatekeeper rule saying termination is only valid if you follow the Contract’s own procedure.

- Clause 15 – Termination by Employer: what the Employer can do when the Contractor is in serious default, and how to value and close out the work.

- Clause 16 – Suspension and Termination by Contractor: the Contractor’s escape routes when the Employer is in default (non-payment, no access, ignoring DAAB decisions, prolonged suspension, etc.).

- Clause 18.5 & 18.6 – Optional Termination / Release from Performance: the “no-fault exit” doors when Exceptional Events (war, sanctions, major legal changes) make continued performance impossible or illegal.

Those core clauses are hard-wired into other parts of the contract. Almost every serious termination will eventually involve:

- Clause 4.2 – Performance Security (non-renewal, drawing on the bond, timing of calls).

- Clause 14 – Contract Price and Payment (how you calculate what’s due after termination, and when it’s paid).

- Clauses 20 & 21 – Claims, DAAB and Arbitration (how the post-termination money fight is actually resolved).

Clause 1.16 is the quiet clause that powers the whole system. It effectively says:

No improvised routes. No implied termination rights. If the Conditions don’t give you a termination right for a situation, then you don’t have a contractual right to end the Contract for that situation.

That’s exactly what DAABs and arbitral tribunals look for when evaluating a termination:

- Which Sub-Clause did you rely on – 15.2, 15.5, 16.2, 18.5, something else?

- Did you follow its notice, cure period, and timing steps?

- Do your letters and emails clearly anchor back to those clauses, or are they just angry correspondence?

If your file shows a dramatic “we hereby terminate” email with no clause-based trail, you’re already drifting towards a wrongful termination argument.

1️⃣ The generic FIDIC termination “life cycle” (1999 vs 2017)

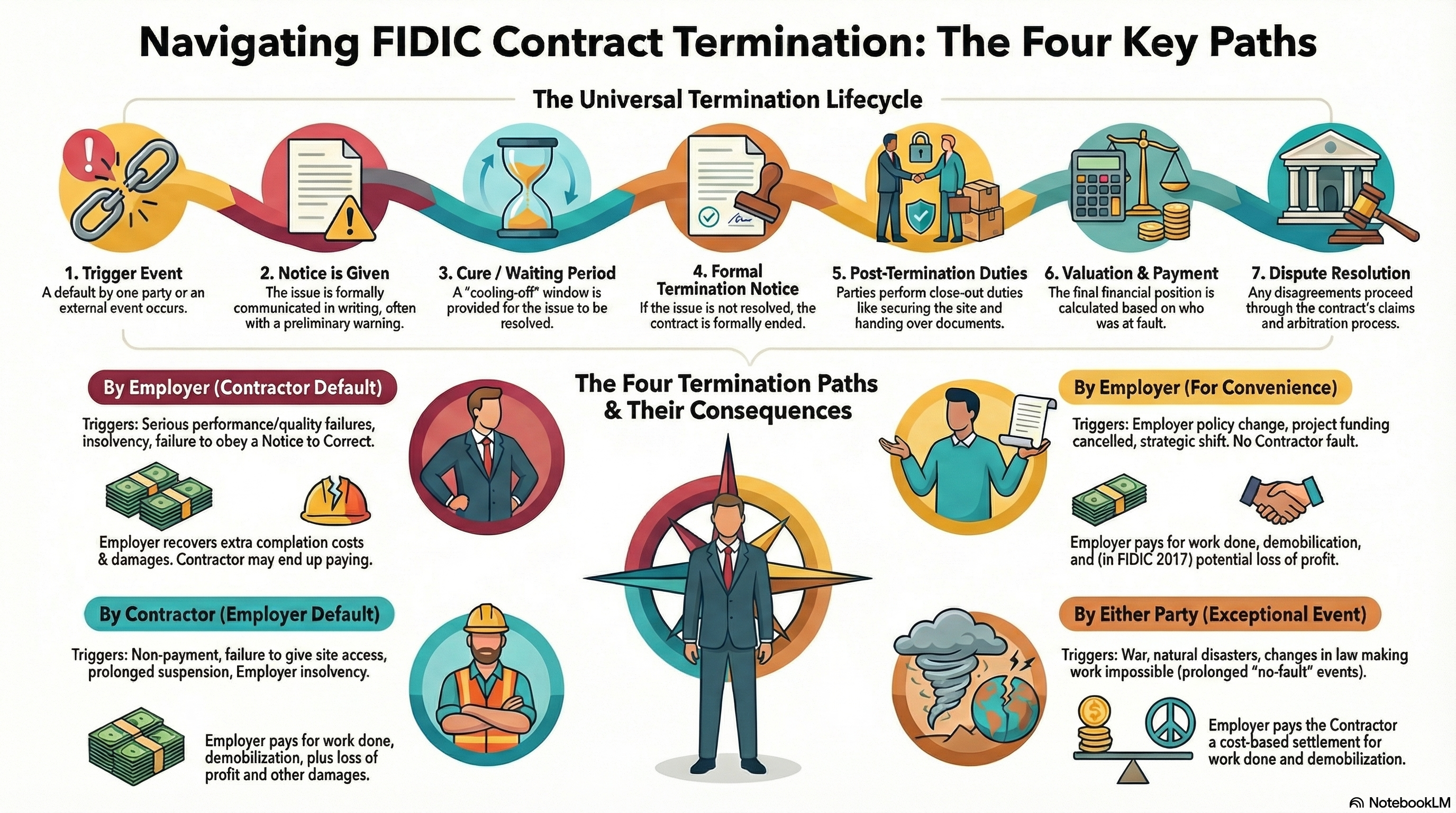

FIDIC doesn’t treat termination as one dramatic explosion but as a repeatable 7-step procedure that appears again and again in Clause 15, Clause 16 and the Exceptional Events provisions.

Every FIDIC termination – whether under Clause 15, Clause 16 or Clause 18 (or Clause 19 in 📘 1999) – runs through the same seven “gates”. If you zoom out, the pattern is always: trigger → notice → cure → formal termination → post-termination duties → valuation & payment → claims / DAAB / arbitration.

1️⃣ A trigger event appears. 2️⃣ A notice is given (and often a Notice to Correct first). 3️⃣ A cure / waiting period runs. 4️⃣ A formal termination notice is issued. 5️⃣ The Parties perform post-termination duties (site, documents, plant). 6️⃣ The Engineer / Parties carry out valuation and payment. 7️⃣ Any dispute goes through the claims and DAAB / arbitration route. Let’s walk through each gate and contrast 📘 1999 with 📒 2017 as we go.

Every termination story starts with a trigger – but the flavour of the trigger tells you which clause family you are in:

-

Employer termination path (Clause 15)

Triggered by Contractor default: serious delay, defective work, failure to obey a Notice to Correct (Clause 15.1 in 📒 2017 / 📘 1999), HSE violations, unlawful acts, insolvency, failure to maintain Performance Security under Clause 4.2, etc. -

Contractor termination path (Clause 16)

Triggered by Employer default: non-payment of amounts certified under Clause 14, failure to give access/possession under Clause 2.1, failure to provide evidence of financial arrangements under Clause 2.4, prolonged suspension, or Employer insolvency. -

No-fault / Exceptional Event path (Clause 18.5 / 18.6 in 2017, Clause 19.6 in 1999)

Triggered by force-majeure-type situations: war, embargo, natural disasters, or changes in law that genuinely prevent performance. Here, the idea is: “it’s nobody’s fault, but we can’t go on like this.”

Once you’ve spotted the trigger, FIDIC expects you to speak up in writing. There are usually two levels of notice in the Employer-default scenario and often at least one in the Contractor-default scenario:

-

Preliminary / corrective notice

For Contractor default, that’s normally the Notice to Correct under Clause 15.1. The Engineer:- Identifies the breach (e.g. persistent failure to meet the programme, serious defects, HSE breach).

- States what must be corrected and by when.

-

Termination-related notice

- Under Clause 15.2 (Employer), the Employer sends a notice invoking Contractor default grounds.

- Under Clause 16.2 (Contractor), the Contractor sends a notice invoking Employer default grounds.

- Under Clause 18.2–18.5, both Parties notify Exceptional Events and, after long duration, may notify intention to terminate.

- 1999: the notices are there, but the structure is leaner and the language a bit more open-ended. The link to dispute machinery is mainly through Clause 20.1 (Contractor’s Claims) and the DAB provisions.

- 2017: the drafting is much more system-shaped:

- Clause 1.3 tightens requirements on Notices and other communications (address, form, method).

- The notice provisions in Clauses 15, 16, 18 are cross-connected with Clause 20 (Claims) and Clause 21 (DAAB and Disputes).

- The idea is to leave less room for improvisation and more for traceable, auditable steps.

Termination is rarely “instant” under FIDIC. Both Books deliberately build in a cooling-off window:

- After a Notice to Correct under Clause 15.1, the Contractor gets a specified time (e.g. 14 days, but the Engineer must state the period) to cure the breach.

- After a non-payment notice under Clause 16, the Employer usually has a defined number of days after the final date for payment to remedy.

- For Exceptional Events, Clause 18 (and Clause 19 in 1999) requires a minimum continuous or aggregated period of prevention (e.g. 84 days or a similar threshold) before optional termination rights arise.

This window is not just “nice to have”; it serves three functions:

- Fairness – gives the defaulting Party a real chance to put things right.

- Evidence – creates a clear timeline: trigger → notice → no cure.

- Risk management – sometimes a serious default is actually fixable at far lower cost than termination; the cure period lets senior management intervene.

- 1999: cure and waiting periods are present but often wrapped in phrases like “if the Contractor fails to remedy within a reasonable time specified in a notice”.

- 2017: you see more explicit durations, cross-references and conditions tying into the claim procedure in Clause 20 and the DAAB decision windows in Clause 21.

Usually, no – not safely. You would still want to point to specific wording that allows immediate termination (e.g. certain insolvency or corruption events) and even then, tribunals often expect you to behave consistently with the FIDIC structure.

If the breach or event isn’t cured, and the waiting periods have run, the next gate is the actual termination notice, for example:

- Employer: notice under Clause 15.2 [Termination for Contractor’s Default] or Clause 15.5 [Termination for Employer’s Convenience].

- Contractor: notice under Clause 16.2 [Termination by Contractor].

- Either Party: notice under Clause 18.5 [Optional Termination] after prolonged Exceptional Events (Clause 19.6 in 📘 1999 Yellow Book).

That notice should:

- Clearly say “we are terminating”, not just “we are considering” or “reserving our rights”.

- Identify which clause is being relied upon (15.2, 15.5, 16.2, 18.5, etc.).

- Specify whether termination is for the whole of the Works or just a Section / part.

- Identify the effective date (often “on receipt” or a stated date).

From this point, the Contract is no longer about delivery of the Works. It becomes a close-out, valuation, and dispute contract.

For instance, the Employer says “we terminate under Clause 15.2 for your default, but also for convenience under Clause 15.5”. That can backfire badly in a dispute – it looks uncertain and can help a Contractor argue that the Employer did not genuinely rely on a valid default ground.

After the termination notice, both Parties have practical duties. This is where the contract stops being theory and becomes logistics:

-

Contractor obligations (after Employer termination under Clause 15.2 or optional termination under Clause 18):

- Stop work except for safety and protection measures.

- Secure the Site and partially completed Works.

- Remove most of the Contractor’s Equipment (unless the Employer instructs otherwise).

- Hand over drawings, documents, test records, etc., as required under Clause 4.1 and related provisions.

- Assign or novate certain subcontracts, if the Contract so provides.

-

Employer rights and obligations:

- Take over the Site and the Works (to the extent not already taken over under Clause 10).

- Use Temporary Works, Plant and Materials belonging to the Contractor, to the extent allowed and valued under Clause 15.3 / 16.4 / 18.5.

- Make the Site available for completion by replacement contractors.

- Co-operate in demobilisation, customs, and export of Contractor’s remaining Equipment.

- 1999: the framework is there but less explicit; much is left to implication and general law.

- 2017: duties are spelled out in more detail and linked more tightly to valuation and claim procedures, making it easier for a DAAB to see who complied and who didn’t.

After the dust settles on Site, the big question is: who owes whom what? This is where Clause 15.3 / 15.4 / 15.6 / 15.7 / 16.4 / 18.5 come alive, depending on which path we’re in:

-

Employer termination for Contractor’s default – Clause 15.3 & 15.4

The Engineer values:- Work executed up to termination,

- Plant and Materials the Employer elects to take over,

- Costs of completing the Works with others,

- Other losses/damages that the Contract and law allow.

-

Employer termination for convenience – Clause 15.6 & 15.7

The Contractor typically recovers:- Payment for work properly executed,

- Reasonable demobilisation and close-down Cost,

- Possibly some profit on work done (but not normally on the work not done, unless Particular Conditions say so).

-

Contractor termination – Clause 16.4

The Contractor is entitled to:- Payment for work done,

- Value of Plant and Materials,

- Demobilisation and “release” costs,

- And often, compensation for the loss and damage caused by Employer’s default within the Contract and legal limits.

-

No-fault Exceptional Event termination – Clause 18.5 / 18.6 (or 19.6 in 1999)

The structure is Cost-based – the Contractor recovers defined Cost items and demobilisation, but typically no damages for lost profit, since no one is at fault.

it ties valuations and entitlements to the claims procedure in Clause 20 and to the DAAB’s decision role in Clause 21, so that termination entitlements are not handled as vague “equity”, but as structured, claim-driven outcomes.

Even if both Parties follow the termination steps perfectly, they may still disagree over:

- Whether there was a valid ground to terminate;

- Whether the terminating Party obeyed the notice / cure machinery;

- How the valuation under Clause 15.3, 16.4, or 18.5 should be calculated.

Under the 📒 2017 Yellow Book:

- Clause 20: Each Party’s termination-related financial claims must follow the Notice of Claim and Fully Detailed Claim mechanics, including the 28-day and 84-day structures (for Contractor) and mirror-style for Employer.

- Clause 21: Disputes go to the DAAB for a decision, then to amicable settlement, and finally to international arbitration (unless Particular Conditions say otherwise).

📘 1999 does the same work but under a different numbering and a slightly lighter architecture (e.g. Clause 20.4 DAB, 20.6 arbitration). The 2017 Book is really a more disciplined, more integrated “claims and disputes engine”.

The Party whose story matches that sequence cleanly is normally in a much safer place.

2️⃣ Termination by Employer for Contractor’s default – end-to-end

The Employer is losing patience and wants to know: “Can we terminate under Clause 15… and will it stand up in front of a DAAB or arbitrator?” In both 📘 1999 and 📒 2017 Yellow Book, termination for Contractor’s default is a sequence – not one angry letter.

At a high level, the journey for Employer termination runs like this: 1) Build your record of default (progress, quality, HSE, security, etc.). 2) Issue a proper Notice to Correct under Clause 15.1. 3) Move into a Clause 15.2 notice when the problem is still not fixed. 4) Use the cure/notice structure (including the special immediate-termination cases in 2017). 5) After termination, take control of the Site and Works under 15.2.3/15.2.4 (2017) or the equivalent 1999 text. 6) Then run valuation and netting-off under 15.3 and 15.4 (1999 & 2017), linked to 2.5/20.* claims mechanisms.

No tribunal will look at a termination in isolation. They will always ask: “What was going on in the months before the termination letters started?” That story is usually written across:

-

Time and programme

Repeated late submissions and late approvals of programme under Clause 8.3 (1999 & 2017). Failure to achieve progress in line with Time for Completion under Clause 8.2 and the latest accepted programme. -

Quality and defects

Persistent non-compliance with Clause 7 – rejection and remedial work, failures to follow instructions, rework that never really gets completed. -

Performance Security and financial comfort

📘 1999: not providing or not topping-up the Performance Security under Clause 4.2 is already a trigger under Clause 15.2(a).

📒 2017: even sharper – repeated failure to comply with performance security obligations is both a serious breach and a specific ground in Sub-Clause 15.2.1(e). -

Decisions and determinations (only really explicit in 2017)

Under 📒 2017, failure to comply with:- a Notice to Correct,

- a binding 3.7 determination, or

- a DAAB decision under 21.4,

So, before anyone writes a “termination” letter, good practice is:

- A trail of Engineer’s instructions, minutes, emails, and letters;

- Clear links from those documents back to actual clauses (time, quality, security, HSE, etc.);

- Evidence that the Contractor understood the risk and failed to put things right.

This is the raw material for your Notice to Correct.

This is the “yellow card” before the red card.

- If the Contractor fails to carry out any obligation under the Contract, the Engineer may give a notice requiring the Contractor to remedy that failure in a specified reasonable time.

- There is no rigid prescription for:

- What exactly the notice must contain;

- How long the “reasonable time” is;

- Whether failure to comply automatically escalates into termination.

So under 1999, the quality of drafting of the Notice to Correct is crucial. Two or three vague lines like “progress is slow, kindly expedite” will not give you a strong launchpad into Clause 15.2.

- The “Notice to Correct” must:

- Describe the Contractor’s failure,

- Point to the relevant Sub-Clause(s) or provisions that create the obligation, and

- Specify a time to remedy, which must be reasonable, taking into account:

- the nature of the failure,

- the work required to fix it, and

- any interim measures needed to protect life, property, or the Works.

- It also labels this notice formally as the “Notice to Correct” in the Conditions.

Practically, this does two things:

- It gives the Contractor a crystal-clear to-do list and a real chance to recover.

- It gives the Employer a very neat exhibit for the DAAB/arbitration bundle later: “Here is the specific obligation; here is the breach; here is the time we gave them.”

If the Contractor does not remedy, or if there is another serious event (like insolvency), we move into Clause 15.2 territory.

- Lists several classic grounds. In simplified form, the Employer may terminate if the Contractor:

- Fails to comply with 4.2 [Performance Security] or a 15.1 Notice to Correct;

- Abandons the Works or clearly shows they don’t intend to continue;

- Without reasonable excuse:

- Fails to proceed in line with Clause 8 (time and programme), or

- Fails to comply with a 7.5 [Rejection] or 7.6 [Remedial Work] notice within 28 days;

- Subcontracts the whole Works or assigns the contract without required agreement;

- Enters into insolvency/receivership/arrangements with creditors or similar events;

- Or for any other serious default described in the full clause.

The termination notice under 1999 normally bundles together reference to Clause 15.2, identification of which sub-paragraph(s) apply, and a statement that the Employer is terminating the Contract. It does not formally split 15.2 into “Notice” and “Termination” sub-clauses – it’s more compact, which puts more pressure on your drafting to show a clear sequence from 15.1 → 15.2.

- Separates the process more cleanly:

- 15.2.1 [Notice] – first notice, listing the specific grounds;

- 15.2.2 [Termination] – second notice that actually terminates (except in special immediate cases).

- The list of grounds in 15.2.1 is longer and sharper than 1999. In summary, the Employer may rely on 15.2.1 where the Contractor, for example:

- Fails to comply with a Notice to Correct 15.1, a binding 3.7 determination, or a DAAB decision under 21.4, and that failure is a material breach;

- Abandons the Works or clearly intends not to perform;

- Without reasonable excuse, fails to:

- proceed in accordance with Clause 8, or

- follow notices and instructions under Clause 7 (quality), especially when delay would push delay damages over any contractual maximum;

- Fails to comply with 4.2 [Performance Security];

- Subcontracts or assigns in breach of 4.4 [Subcontractors] or 1.7 [Assignment];

- Becomes insolvent or subject to equivalent insolvency measures;

- In a JV, one member hits an insolvency or severe default and the others don’t step in as required;

- Is reasonably found to have engaged in corrupt or fraudulent practice.

So 2017 connects the Employer’s termination right directly to performance security failures, refusal to obey binding decisions, extreme delay, and integrity breaches. It makes it much easier for the Employer to say: “We walked through 3.7, DAAB, notices, and you still ignored us. That’s a termination ground in its own right.”

Now comes the critical red-card moment.

- Under 15.2.2 [Termination]:

- If the Contractor does not remedy the matter specified in the 15.2.1 Notice within 14 days of receiving it,

- The Employer may issue a second notice that immediately terminates the Contract.

- The termination date is the date the Contractor receives this second notice.

- For the most serious grounds – unauthorised subcontracting/assignment, insolvency events, corrupt/fraudulent practice – the Employer may terminate immediately:

- A single notice under 15.2.1 can simultaneously identify the ground and state that the Contract is terminated with immediate effect.

So 2017 essentially says: “normal” breaches → two-step (15.2.1 notice + 14 days → 15.2.2 termination notice); extreme breaches (f, g, h) → one-step termination.

- You rely on the prior 15.1 Notice to Correct and correspondence to show you gave a reasonable chance to remedy.

- Then you issue a 15.2 termination notice, which states the grounds (15.2(a)–(e) etc.) and confirms termination with effect from a stated date or from receipt.

- The two-step structure is not spelled out, so procedure becomes even more important:

- If you move too quickly from first complaint to 15.2 notice, a tribunal might say “cure period was not reasonable”.

- If your 15.1 notice was vague, the Contractor can argue they were never told exactly what to fix.

“Show us the sequence of letters, instructions, notices and replies between the first red flag and the termination.”

Once the Contract is terminated for Contractor’s default, FIDIC pivots to site control and handover.

- After termination, the Contractor must immediately obey reasonable instructions in the termination notice, especially regarding:

- assignment of subcontracts;

- protection of life, property, and the Works.

- They must deliver to the Engineer:

- Goods required by the Employer;

- all Contractor’s Documents;

- all other design documents produced by or for the Contractor.

- They must leave the Site. If they don’t, the Employer can expel them.

- The Employer may complete the Works itself or bring in new entities, and may use:

- Contractor’s design documents,

- Goods and other items acquired for the Works,

- Once completion is done, the Employer must give notice to the Contractor to remove any remaining Equipment; if money is owed and the Contractor does not act, the Employer may (where law allows) sell items and apply proceeds to amounts due.

- After termination under 15.2, the Employer may:

- take possession of Contractor’s Plant, Materials, and Temporary Works on Site for the purpose of completing the Works;

- order assignment of certain subcontracts;

- complete the Works itself or appoint others.

- If the Contractor fails to pay sums due, the Employer can, within legal limits, sell Contractor’s property taken over and apply proceeds first to its own losses, then return surplus.

Both editions share the same concept: once termination for default happens, the Employer becomes project manager and “asset manager” – using what the Contractor has left behind to finish the job and recover its losses.

Now we move from “who is on Site” to “who owes whom what”.

- After termination under 15.2, the Engineer must act under 3.7 [Agreement or Determination] to agree/determine the value of:

- The Permanent Works executed up to the termination date;

- Goods the Employer requires;

- Contractor’s Documents and design documents to the extent used for completion;

- Other items relevant to the valuation rules.

- The valuation reflects:

- the same principles as normal payment (as if moving towards final payment under 14.13),

- plus any additions/deductions, including retention and previous payments.

- Defective or non-compliant works and documents are excluded or valued appropriately at a reduced figure.

- The date of termination is the reference point for the 3.7.3 time limit – pulling the whole termination valuation inside the claims/determination process with defined timelines.

- After termination, the Engineer must value the Works and Goods executed/delivered at the date of termination.

- The principles refer back to Clause 12 (measurement and evaluation), Clause 14 (payment), and any relevant rates/prices.

Both editions, in effect, create a “snapshot” of the Contractor’s entitlements at the termination date. The difference is that 2017 tightly embeds this into the 3.7 determination process, while 1999 relies on the more general 3.5 [Determinations] framework.

This is where the commercial “sting” of termination for Contractor’s default really lives.

- Once 15.3 valuation is done, the Employer may withhold payment of the 15.3 amount until it has established:

- its additional costs,

- its losses and damages, and

- any outstanding delay damages.

- Subject to Clause 20.2 [Claims for Payment and/or EOT], the Employer is then entitled to payment by the Contractor of:

- Additional costs of executing the Works, including bringing in replacement contractors, extra supervision, design, logistics, and site reinstatement costs.

- Any losses and damages suffered in completing the Works.

- Delay damages, if the Works or a Section had not been taken over under 10.1 and the termination date fell after the Time for Completion.

- The Employer then sets off the Contractor’s “credit” (the 15.3 valuation) against the Employer’s “debit” (extra completion cost, losses, damages, delay damages).

- If the Employer’s losses exceed the Contractor’s credit, the Contractor owes money – recoverable via:

- calling the Performance Security under 4.2,

- set-off against any unpaid certified amounts,

- or a direct claim via the dispute resolution pathway.

- If – rarely – the Contractor’s credit exceeds Employer’s losses, the Employer must pay the balance to the Contractor.

- Employer’s recovery is expressly subject to the claims procedure in Clause 20 – the Employer must walk through notice and substantiation steps just like the Contractor.

- After a 15.2 termination takes effect, the Employer may:

- Proceed under 2.5 [Employer’s Claims];

- Withhold further payments until its extra completion costs and other costs are known;

- Recover from the Contractor the extra costs of completing the Works and losses/damages incurred due to Contractor’s default.

- Only after recovering those amounts does the Employer have to pay any balance of the 15.3 valuation to the Contractor.

If the Employer does not keep good records of completion costs – replacement contract sums, supervision hours, variation breakdowns, and delay impact – much of the “extra cost” claim can crumble, even if termination itself was lawful.

Imagine you’re Employer on a design-build plant project:

- For months, you’ve seen poor progress, missed key dates, and non-compliance with performance security renewals.

- You’ve issued programme comments, instructions, and meeting minutes setting out slippage.

- Things worsen. You issue a 15.1 Notice to Correct:

- It lists the specific failures (non-renewal of performance security, failure to comply with 3.7 determination on extra works, and lack of progress).

- It calls out clause numbers.

- It gives the Contractor a defined number of days to put things right.

- The Contractor does a few superficial things but doesn’t renew the security, doesn’t follow the determination, and still lags badly.

- You issue a 15.2.1 Notice (2017) or a 15.2-based notice (1999), clearly listing the grounds.

- In 2017:

- If it’s “normal” default, you give 14 days under 15.2.2 before the termination.

- If it’s insolvency or proven corruption, you may terminate immediately using one notice.

- You terminate, take over Site, assign key subcontracts, and appoint a replacement Contractor.

- The Engineer carries out a 15.3 valuation, then the Employer runs its claims under 15.4 and Clause 20/2.5, netting off extra completion cost and delay damages.

- The Contractor disputes both the validity of termination and the quantum, and it goes to DAAB and then possibly arbitration.

Who is in the stronger position? The Party who:

- treated Clause 15 as a carefully signposted process,

- used clean, clause-based notices, and

- kept a clear record of costs and causal links.

- Don’t jump straight to “we want to terminate” – build your paper trail, understand which sub-paragraphs of 15.2 you’re relying on, and use 15.1 properly.

- Draft Notices like exhibits you will be happy to see on a DAAB/arbitration screen two years from now – clause references, facts, dates, cure periods.

- Treat the valuation and claims phase (15.3/15.4 + 2.5/20.*) as part of the termination process from day one – not an afterthought.

- Always ask yourself: “If we get this wrong and the tribunal calls it a wrongful termination, are we ready for the consequences?”

3️⃣ Termination by Employer for convenience – a different animal 🐘

Now let’s talk about the “odd one out” in the termination family: termination not because the Contractor has done anything wrong, but simply because the Employer wants to stop. Think of Sub-Clause 15.5 in both editions as the “political / funding parachute”.

In “convenience world”, the classic triggers are: government policy shifts 🏛️, funding evaporation 💸, strategy changes, or scope becoming redundant. FIDIC basically tells the Employer: “Fine, you can pull the plug for convenience… but you don’t get to do it cheaply, and you don’t get to quietly recycle the Contractor’s work.”

Before anyone even mentions Clause 15.5, you really want to be clear internally:

- Are you genuinely stopping the project (or a proper part of it)?

- Or are you simply fed up with the Contractor and trying to avoid the fight under Clause 15.2?

Because:

-

If it’s Contractor default, you’re in Clause 15.1 / 15.2 world:

Notice to Correct, cure period, evidence, valuation under 15.3, Employer recovers extra completion cost under 15.4. -

If it’s no-one’s fault, you’re in Clause 15.5 world:

Employer carries the bill for close-down; Contractor is not treated as “the bad guy”.

A very practical test you can use with your team:

“If we call this convenience, are we prepared to pay: – all work done, – demobilisation and close-down Cost, – and (in 2017) potentially loss of profit on the unperformed portion?”

If the answer is no, you probably aren’t really doing a 15.5 termination – you’re trying to run a default case without the admin.

- The Employer may terminate the Contract at any time for its own convenience, by notice to the Contractor.

-

Termination takes effect after a delay of 28 days from the later of:

- the date the Contractor receives that notice, or

- the date the Employer returns the Performance Security.

- After a 15.5 termination, the Contractor must follow Clause 16.3:

- Stop work (except for safety / instructed close-down tasks),

- Hand over documents and works for which it has been paid,

- Remove other Goods and leave the Site.

- The Contractor’s money rights are then dealt with under Clause 19.6 [Optional Termination, Payment and Release], even though there may be no Force Majeure – FIDIC borrows that financial logic for convenience termination.

- Crucially, 1999 makes it crystal clear that the Employer is not supposed to use 15.5 as a sneaky way to terminate and then hand the same Works to another contractor at a lower price. That “no cheap re-tender” message is baked into the text.

- The Employer can terminate at any time for convenience by giving a notice which expressly says it is issued under Sub-Clause 15.5.

- Immediately after issuing that notice, the Employer must:

- Stop treating the Contractor’s design and documents as if they are freely reusable. They can still be used for payment / valuation and close-out, but not as an ongoing design resource for completing the project.

- Stop using the Contractor’s Equipment, Temporary Works, access, and other facilities under Clause 4.6.

- Make arrangements to return the Performance Security.

- Termination takes effect 28 days after the later of:

- the Contractor receiving the 15.5 notice, or

- the Performance Security being returned.

- The really important 2017 twist: until the Contractor has actually received the amount due under Sub-Clause 15.6, the Employer must not execute any part of the Works itself or get any other entity to execute any part of them.

So:

- 📘 1999: “Don’t use 15.5 as a disguised re-tender tool.”

- 📒 2017: “You can re-tender later, but only after we have calculated and actually paid what the Contractor is owed.” That’s a big shift in how FIDIC protects the Contractor’s financial position.

After a 15.5 termination takes effect, the Contractor’s obligations in both editions are channelled through Clause 16.3.

- Once termination under 15.5 (or Contractor termination, or Optional Termination) has taken effect, the Contractor must promptly:

-

Stop all further work, except what is essential:

- to protect life or property, and

- to keep the Works safe and stable.

-

Hand over to the Employer:

- Contractor’s design documents,

- Plant, Materials, and other work items for which the Contractor has already been paid.

- Remove all other Goods from the Site (except what must stay for safety) and leave the Site.

-

Stop all further work, except what is essential:

- The 2017 text is extremely similar:

- Stop further work, except:

- essential safety / protection; and

- any particular “wrap up” or safety work instructed by the Employer/Engineer (paid as Cost Plus Profit under Clause 20.2).

- Deliver to the Engineer all documents, Plant, Materials and other work for which the Contractor has been paid.

- Remove all other Goods and vacate the Site.

- Stop further work, except:

So in both Books, termination for convenience is not a licence for the Contractor to just walk away. There is a tidy and disciplined close-down, and the Contractor gets paid for these close-down activities too (either via 19.6 in 1999 or 18.5 / 15.6 / 20.2 in 2017).

- Under 1999, a convenience termination sends you to Clause 19.6 for the money part. The Engineer must determine (and certify):

- 1. Amounts for work done – normal contract value for the Works properly executed up to the termination date.

- 2. Cost of Plant and Materials ordered for the Works – provided they were genuinely ordered for the project, are reasonable in quantity, and become the property and risk of the Employer once paid for.

- 3. Other reasonable costs and liabilities – expenditures reasonably incurred by the Contractor in expectation of completing the Works, e.g.:

- de-mobilisation,

- off-site design efforts,

- cancellation charges,

- certain head-office costs linked to the project.

- 4. Cost of removing Temporary Works and Contractor’s Equipment – including transport off Site or back to home country (or other location if no more expensive).

- 5. Cost of repatriation of staff and labour who were solely on the project at the date of termination.

- After these are calculated and certified, the Employer pays them, and both Parties get a clean legal “release” from further obligations (subject to any pre-existing breaches).

- Notice what isn’t clearly there for Employer convenience under 1999: an express entitlement to loss of profit on the unexecuted portion of the Works. You might argue for it under local law, but FIDIC’s own wording nudges the result towards cost recovery, not profit on work not done.

- 2017 does something quite bold. It splits out the valuation and payment rules specifically for convenience termination.

- Sub-Clause 15.6 – Valuation after Termination for Employer’s Convenience

After a 15.5 termination:- The Contractor must submit detailed particulars (with whatever backup the Engineer reasonably asks for) of:

-

(a) Value of work done, which includes:

- The items equivalent to Optional Termination under Clause 18.5: work executed, ordered Plant and Materials, reasonable costs and liabilities incurred in expecting to complete the Works, demobilisation, repatriation, etc.

- Plus any other additions/deductions and the balance due if the Contract were moving into final account.

- (b) Loss of profit and other losses/damages specifically caused by this termination.

-

(a) Value of work done, which includes:

- The Engineer then uses Clause 3.7 [Agreement or Determination] to agree or determine those amounts. The 3.7.3 time limit clock starts from receipt of the 15.6 particulars.

- The Engineer issues a Payment Certificate for the amount agreed/determined, without the Contractor needing to submit a normal Statement.

- The Contractor must submit detailed particulars (with whatever backup the Engineer reasonably asks for) of:

- Sub-Clause 15.7 – Payment after Termination for Employer’s Convenience

- The Employer must pay the amount certified under 15.6 within 112 days after the Engineer received the Contractor’s submission.

- The Limitation of Liability clause in 2017 (Clause 1.15) carves out Sub-Clause 15.7 from the normal “no loss of profit / indirect loss” shield.

- That means that for convenience termination, the Contractor’s loss of profit and other termination-induced losses are deliberately left on the table – the Employer can’t hide behind the general limitation-of-liability shield for this scenario.

So in simple terms:

- 📘 1999: convenience termination → Contractor mainly gets costs and demobilisation via 19.6; profit on the “never performed” portion is less clearly supported by the contract text.

- 📒 2017: convenience termination → Contractor gets:

- value of work done + demobilisation / closure costs, and

- potential loss of profit and other losses/damages caused by the termination,

In 2017, convenience termination is not a “side door” outside the claim system. It is fully integrated into the Clause 20 / 21 architecture:

-

The Contractor’s 15.6 submission is essentially a super-detailed Claim:

- It goes through agreement/determination under 3.7,

- Can then become a Dispute under Clause 21,

- And ultimately a DAAB decision and, if needed, arbitration award.

- The Employer’s “no re-tender until you pay” constraint under 15.5 gives the Contractor leverage: if there is delay or reluctance to pay, the Employer is stuck; it can’t legally proceed with replacement works without creating a breach of 15.5 that will be very visible to a DAAB.

In 1999, the path is via:

- 19.6 valuation and Payment Certificate,

- Any disagreement going through Clause 20.1 (Contractor’s Claims) and then the DAB/arbitration machinery.

The structural idea is the same, but 2017 is far more procedural and claims-friendly.

Scenario A – Employer genuinely cancels the project

A metro extension is shelved due to a political decision. Only 30% of the Works are done.

- Under 📘 1999:

- Employer may terminate under 15.5,

- Contractor demobilises under 16.3,

- Engineer values under 19.6:

- work done,

- committed Plant and Materials,

- reasonable costs/liabilities in expectation of completing,

- demobilisation + repatriation.

- Under 📒 2017:

- Employer uses 15.5 and follows notice/Performance Security steps,

- Contractor submits 15.6 particulars:

- (a) all the 18.5-style cost items, plus

- (b) claimed loss of profit and other damages caused by the project being cancelled.

- Engineer issues a 3.7 determination and Payment Certificate; Employer pays within 112 days.

- Only then can Employer think about re-starting a smaller successor scheme with someone else.

Scenario B – Employer tries to “swap” contractors mid-stream using 15.5

Employer is unhappy with Contractor performance but is nervous about a full 15.2 default termination case. They think: “Let’s just use 15.5, pay them something, and retender quickly.”

- Under 📘 1999: The wording strongly discourages using 15.5 as a tool to terminate so that the Employer can execute or re-let the same Works. An arbitral tribunal can easily see through a paper-thin “convenience” story if there was an obvious intent to re-let.

- Under 📒 2017: The Employer cannot execute or re-let any part of the Works until the Contractor has been paid the full amount determined under 15.6. If the Employer jumps the gun, it is now in breach of 15.5 itself, handing the Contractor a tidy claim.

So, if the real aim is removing a non-performing Contractor and hiring a better one to finish the same Works, the correct – and safer – route is usually Clause 15.2, not 15.5.

Scenario C – Contractor wants compensation for lost profit

After a 2017 convenience termination, the Contractor submits a 15.6(b) claim for:

- overhead recovery,

- loss of profit on the unexecuted portion,

- demobilisation inefficiencies,

- idle plant costs, etc.

The Employer replies: “No, Clause 1.15 says you can’t claim loss of profit or indirect loss.”

But Clause 1.15 itself carves out 15.7 as an exception. So the Contractor has a strong contractual basis to say:

“In this very specific situation – Employer convenience termination – FIDIC deliberately allows profit and other losses to be claimed.”

Whether the full amount claimed is awarded is a separate, evidence-based question, but the door is open in 2017 in a way it simply wasn’t in 1999.

For Employers:

- Treat 15.5 as a policy/funding emergency exit, not a casual tool.

- Be prepared to explain to a DAAB why your decision was indeed convenience, not disguised default.

-

Plan the cash flow: in 2017 you may be paying:

- full cost of work done,

- demobilisation and close-down,

- and a slice of lost profit – all within 112 days of the Contractor’s submission.

- Build internal guidance: “If we’re not happy with Contractor performance, we go down 15.1/15.2; we only use 15.5 when the project itself is pulled or materially re-scoped.”

For Contractors:

- Don’t panic when you see a 15.5 notice. This is not an allegation of breach – it is actually a protective clause for you in many ways.

- In 📘 1999, prepare a 19.6-style close-down claim (work done + committed plant + reasonable costs + demob + repatriation).

-

In 📒 2017, prepare a forensic 15.6 submission:

- Clear split between (a) cost-style items and (b) loss of profit / other damages.

- Support both with proper evidence (programmes, resource histograms, plant utilisation, head-office allocations).

- Keep a close eye on whether the Employer tries to retender too early or to continue the Works before you’re fully paid – that can itself become a strong additional claim.

4️⃣ Termination by Contractor – when the Employer is in default

Clause 16 is the Contractor’s “nuclear option”. Used well, the 16.1 + 16.2 sequence is a powerful lever to fix non-payment, ignored DAAB decisions and prolonged suspensions.

4.1 Big picture – how “Contractor termination” is structured

Up to now we’ve been looking at termination with the Employer in the driving seat. But FIDIC is supposed to be a balanced form – so the Yellow Book also gives the Contractor a nuclear option when the Employer is the one in default.

Contractors often underestimate how powerful Clause 16 actually is. Even if you never pull the trigger, a well-handled Sub-Clause 16.1 + 16.2 sequence is a huge lever in getting payments moving, DAAB decisions respected, and prolonged suspensions resolved.

In both editions you’ve got the same core architecture:

- Clause 16 – Suspension and Termination by Contractor

- Sub-Clause 16.1 – right to suspend or slow down the work.

- Sub-Clause 16.2 – right to terminate if serious Employer default continues.

- Sub-Clause 16.3 – Contractor’s obligations after termination (tidy close-out).

- Sub-Clause 16.4 – money after Contractor termination.

The logic is straightforward:

- Employer misbehaves.

- Contractor warns and applies pressure using 16.1 (suspension).

- If that doesn’t work, Contractor escalates to 16.2 (termination).

- Then 16.3/16.4 + 18.5 / 19.6 kick in to sort out demobilisation and money.

The right way to see it: Suspension under 16.1 is the yellow card; termination under 16.2 is the red card.

4.2 Triggers & timeline in 📘 1999 – Clause 16.1 + 16.2

4.2.1 Step 1 – When can the Contractor suspend under 16.1 (1999)?

Under 1999 Sub-Clause 16.1 [Contractor’s Entitlement to Suspend Work], three classic Employer failings open the door:

- Engineer fails to certify an Interim Payment Certificate under Sub-Clause 14.6.

- Employer fails to give evidence of financial arrangements under Sub-Clause 2.4.

- Employer fails to pay amounts due under Sub-Clause 14.7.

If any of these happen, the Contractor may:

- Give a notice to the Employer;

- Wait not less than 21 days; then

-

Suspend work or reduce the rate of work until:

- the certificate is issued, or

- evidence is produced, or

- payment is actually made.

Suspension does not prejudice the Contractor’s right to:

- Financing charges under Sub-Clause 14.8 [Delayed Payment]; and

- Termination under Sub-Clause 16.2.

If suspension causes delay or Cost, the Contractor can claim EOT and Cost under Clause 20.1 [Contractor’s Claims]. This is the pressure valve FIDIC gives the Contractor: “You’re starving us of cash or comfort? Then we slow or stop the machine.”

4.2.2 Step 2 – When can the Contractor terminate under 16.2 (1999)?

Under 1999 Sub-Clause 16.2 [Termination by Contractor], the Contractor can terminate if any of the following persist:

- (a) No 2.4 evidence – no “reasonable evidence” of financial arrangements within 42 days after giving a 16.1 notice about a 2.4 failure.

- (b) No IPC – Engineer fails, within 56 days after receiving a Statement and supporting documents, to issue the relevant Interim Payment Certificate.

- (c) No payment – Contractor doesn’t receive the amount due under an IPC within 42 days after the final date for payment under 14.7 (ignoring legitimate deductions under 2.5 [Employer’s Claims]).

- (d) Material breach – Employer “substantially fails” to perform its obligations under the Contract.

- (e) Contract Agreement / assignment issues – Employer fails to sign the Contract Agreement (1.6) or improperly assigns in breach of 1.7 [Assignment].

- (f) Prolonged suspension under Sub-Clause 8.11 affecting the whole of the Works.

- (g) Employer insolvency – bankruptcy, liquidation, administration, receivership or similar events.

Then the Contractor has choices:

- In any of these cases, they can give 14 days’ notice to terminate.

- For (f) prolonged suspension and (g) insolvency, the Contractor may terminate immediately by notice – no 14-day wait.

4.3 Triggers & timeline in 📒 2017 – more grounds, more discipline

The 2017 Yellow Book takes the same engine and:

- Adds new triggers that reflect modern disputes (DAAB decisions, Commencement Date, corruption);

- Builds in material breach tests; and

- Ties everything into the Clause 20 claims and Clause 21 DAAB framework.

4.3.1 Step 1 – Suspension under Sub-Clause 16.1 (2017)

2017 Sub-Clause 16.1 [Suspension by Contractor] opens the door if any of these happen:

- (a) Engineer fails to certify under Sub-Clause 14.6 [Issue of IPC].

- (b) Employer fails to provide reasonable evidence under Sub-Clause 2.4 [Employer’s Financial Arrangements].

- (c) Employer fails to comply with Sub-Clause 14.7 [Payment].

-

(d) Employer fails to comply with:

- a binding agreement or final and binding determination under Sub-Clause 3.7 [Agreement or Determination]; or

- a DAAB decision under Clause 21.4 [Obtaining DAAB’s Decision],

Then:

- Contractor gives a Notice under 16.1 to the Employer.

- If the default is not cured, the Contractor may, not less than 21 days after that Notice:

- suspend work; or

- reduce the rate of work.

Again, this doesn’t prejudice financing charges under 14.8, or the right to terminate under 16.2. If the Contractor suffers delay or Cost due to suspending or slowing down, they can claim EOT + Cost Plus Profit under Clause 20.2.

4.3.2 Step 2 – Notice of intention to terminate – 16.2.1 (2017)

Sub-Clause 16.2.1 [Notice] is the Contractor’s “I’m serious now” notice. The Contractor can give a Notice (stating that it’s under 16.2.1) if:

- (a) No 2.4 evidence within 42 days after a 16.1 Notice about financial arrangements.

- (b) Engineer fails to issue a Payment Certificate within 56 days after receiving a Statement + supporting documents.

- (c) Contractor doesn’t receive amounts due under any Payment Certificate within 42 days after the final date for payment under 14.7.

- (d) Employer fails to comply with a binding agreement or final and binding determination under 3.7, or a DAAB decision under 21.4, and that failure is a material breach.

- (e) Employer “substantially fails to perform” its obligations – the general material breach ground.

- (f) Contractor doesn’t receive a Notice of Commencement Date under 8.1 within 84 days after the Letter of Acceptance.

- (g) Employer fails to comply with 1.6 [Contract Agreement] or makes an unauthorised assignment under 1.7 [Assignment].

- (h) A prolonged suspension affects the whole of the Works as described in 8.12(b) [Prolonged Suspension].

- (i) Employer goes into insolvency / winding-up / reorganisation / similar events.

- (j) Employer is found, based on reasonable evidence, to have engaged in corrupt, fraudulent, collusive or coercive practice in relation to the Works or the Contract.

4.3.3 Step 3 – Actual termination – 16.2.2 (2017)

Under Sub-Clause 16.2.2 [Termination]:

-

For most grounds in 16.2.1, the Employer gets a final chance:

- If the Employer doesn’t remedy the matter within 14 days of receiving the 16.2.1 notice,

- the Contractor may issue a second notice terminating the Contract immediately.

- Termination date = date Employer receives that second notice.

-

For the really serious grounds – (g)(ii), (h), (i) or (j) – the Contractor can terminate immediately with the first 16.2.1 notice:

- certain assignment breaches,

- prolonged suspension of the whole Works,

- insolvency events,

- corrupt/fraudulent/collusive/coercive practice.

If the Contractor suffers delay or incurs Cost during the 14-day cure window, they can claim EOT and Cost Plus Profit through Clause 20.2.

Extreme Employer behaviour (insolvency, corruption, prolonged suspension) can jump straight to one-step immediate termination.

4.4 Step-by-step “movie version” from the Contractor’s side 🎬

Step 1 – Spot the default

You see:

- No IPC issued;

- or payment not made;

- or Employer ignores DAAB decision;

- or no Commencement Date;

- or prolonged suspension; or

- Employer clearly in financial trouble.

First question: “Is this listed in 16.1 or 16.2?”

Step 2 – Use 16.1 like a pressure cooker

-

Serve a neat 16.1 notice:

- identify the Sub-Clause breached (2.4, 14.6, 14.7, 3.7, 21.4);

- say “if you don’t fix this, we will suspend after 21 days under 16.1”.

- If nothing improves, suspend or reduce rate of work. This hits programme, delays handover, and focuses the Employer’s mind.

Step 3 – Escalate to 16.2 / 16.2.1 intention to terminate

If defaults or non-payment continue beyond the 42 / 56 / 42 / 84-day thresholds, issue a clear, clause-based intention notice: “We are giving Notice under Sub-Clause 16.2.1 (or 16.2 in 1999) relying on grounds (a), (b), (d)…”.

This is where lawyers and claims teams start to pay very close attention.

Step 4 – Cure period (where applicable)

Employer has a 14-day grace window (both 1999 and 2017) – except for immediate-termination cases such as prolonged suspension of the whole Works, insolvency events, or corruption (2017).

If the Employer actually fixes the breach (pays, certifies, issues Commencement Date, complies with DAAB decision), termination risk recedes – though the Contractor may still have a claims trail for delay and financing charges.

Step 5 – Pull the trigger: termination notice

If the Employer does not cure, the Contractor issues the termination notice under 1999 Sub-Clause 16.2 or 2017 Sub-Clause 16.2.2.

From that date, the Contractor’s performance obligations on the Works stop (other than close-out duties under 16.3). The Contract transforms into a “close-down and valuation” relationship – leading directly to 16.3, 16.4, and 18.5 / 19.6.

4.5 After termination – Contractor’s obligations under 16.3

Both editions have very similar wording for Sub-Clause 16.3 [Contractor’s Obligations After Termination]. After termination under:

- Employer’s convenience (15.5),

- Contractor’s termination (16.2), or

- Optional termination after Exceptional Events (18.5 / 19.6),

the Contractor must promptly:

- Stop further work, except anything the Engineer has instructed for safety or protection of life/property. That safety work is paid as Cost Plus Profit via the claims clause (20.1 / 20.2).

- Hand over to the Engineer / Employer the Contractor’s documents, Plant, Materials, and other work for which the Contractor has been paid.

- Remove all other Goods from the Site (except what must stay for safety) and leave the Site.

Even when the Contractor terminates, they don’t just vanish. FIDIC expects a tidy demobilisation consistent with safety and handover of what’s been paid for.

4.6 Money after Contractor termination – 16.4 + 18.5 / 19.6

Key question: “If I terminate as Contractor, what do I actually get paid?”

The answer is very Contractor-friendly in both editions – and even more so in 2017.

4.6.1 1999 – Sub-Clause 16.4 [Payment on Termination] + 19.6

Once a 1999 Contractor termination under 16.2 takes effect, the Employer must:

- Return the Performance Security.

-

Pay the Contractor under Sub-Clause 19.6 [Optional Termination, Payment and Release]:

- value of work done,

- value of Plant and Materials ordered and reasonably required for the Works (which then pass to Employer’s ownership and risk),

- reasonable costs and liabilities incurred in expectation of completing the Works,

- demobilisation and removal of Temporary Works and Equipment,

- repatriation of staff and labour engaged solely on the project.

- Plus – critically – pay the Contractor “loss of profit or other loss or damage” the Contractor has sustained because of this termination.

So in 1999, termination by Contractor is like optional termination (no-fault) plus an explicit right to loss of profit and other losses flowing from Employer’s default.

4.6.2 2017 – Sub-Clause 16.4 [Payment after Termination by Contractor] + 18.5

In 2017, FIDIC simplifies but keeps the same idea – and then locks it in via the limitation-of-liability clause:

- After a 2017 termination under 16.2, the Employer must pay the Contractor in accordance with Sub-Clause 18.5 [Optional Termination, Payment and Release]: value of work executed, reasonable costs/liabilities for the purposes of the Works, demobilisation, removal of Temporary Works/Equipment, repatriation of staff and labour, etc.

- And – subject to the claims procedure in 20.2 – the Employer must pay loss of profit, and other losses and damages suffered by the Contractor because of this termination.

Then Clause 1.15 [Limitation of Liability] does something very important: it excludes Sub-Clause 16.4 from the usual “no loss of profit / no indirect loss” shield (along with 15.7, 17.3 and some indemnities).

In normal claims, Employers can often rely on 1.15 to say “no profit / no consequential loss”. But when the Contractor terminates under 16.2, that shield does not apply – FIDIC wants the Contractor to be able to recover lost profit and other termination-linked losses, on top of the optional-termination “cost” items.

4.7 What-if scenarios – how Contractor termination plays in practice

Scenario A – Chronic non-payment of IPCs

IPC issued for a large amount. Final date for payment under 14.7 passes. 42 days after that final date, still nothing paid.

Contractor path:

- Serve 16.1 notice (non-payment) → after 21 days, slow or suspend work.

- Once the 42-day threshold is crossed, serve 16.2 (1999) or 16.2.1 (2017) notice of intention to terminate.

- If still unpaid after the 14-day cure window → terminate.

- Claim under 16.4: optional-termination style costs, plus loss of profit and other damages due to Employer’s default.

DAAB/arbitrator will ask:

- Was the IPC valid?

- Were there legitimate Employer set-offs under 2.5/20?

- Did the Contractor obey notice, timing and claims procedures?

If yes, termination by Contractor can be found lawful, and Employer may face a significant damages bill.

Scenario B – Employer ignores DAAB decision ordering payment (2017)

DAAB decision under 21.4 orders Employer to pay a substantial sum. Employer simply refuses.

Contractor path under 2017:

- DAAB decision is a 16.1(d) trigger (failure to comply with DAAB decision = material breach).

- Contractor issues 16.1 Notice → after 21 days, may suspend or slow work.

- If still no compliance, serve 16.2.1(d) notice of intention to terminate.

- After 14 days, if Employer still doesn’t comply → 16.2.2 termination notice.

This route is often more powerful than just going straight to enforcement of the DAAB decision, because it threatens the entire Contract and exposes Employer to 16.4-style loss of profit compensation.

Scenario C – Prolonged suspension of the entire project

Engineer orders suspension of all Works under Clause 8.8 (say, for Employer funding or design reasons). Suspension drags on beyond the “prolonged suspension” threshold in 8.11 (1999) / 8.12 (2017).

This is a ground under 1999 16.2(f) and 2017 16.2.1(h). In both editions the Contractor can terminate immediately once prolonged suspension criteria are met – no extra 14-day grace needed for Employer.

Financially, the Contractor is again in 16.4 + 19.6 / 18.5 territory – but with profit and other losses recoverable because Employer is in default, not because of force majeure.

Scenario D – Employer insolvency

If the Employer becomes bankrupt/insolvent or enters administration / similar processes: in 1999 it’s a 16.2(g) ground; in 2017 it’s a 16.2.1(i) ground.

In both cases the Contractor may terminate immediately, without a 14-day cure. This is pure risk-cutting: FIDIC doesn’t force the Contractor to keep performing for an Employer that clearly cannot pay.

4.8 Practical lessons & drafting tips 💡

For Contractors

- Treat 16.1 as a serious commercial tool, not just a standard complaint letter: reference exact Sub-Clauses, diarise 21 / 42 / 56 / 84 / 14-day thresholds, and think strategically about when to suspend and what to continue (safety, critical preservation works).

- Before terminating, double-check you have complied with your own obligations (programme updates, quality, notices, claims), and make sure the defaults you rely on are clearly documented and objectively provable.

- Walk through the 16.1 → 16.2 timeline with your claims/legal team like a flowchart.

- Remember that under both editions, termination by Contractor moves you into cost recovery via optional termination rules, plus loss of profit and other damages via 16.4 – and in 2017, 1.15 confirms those are not excluded.

For Employers

- When you receive a 16.1 or 16.2 notice, that’s not “noise”; it’s a pre-termination signal. Decide quickly: do we pay, do we comply with the DAAB decision, do we issue the Commencement Date?

- If cash-flow is tight, trying to “manage payments” by systematically breaching 14.7 is extremely risky under FIDIC: you’re not just accruing 14.8 interest; you’re walking towards a Contractor termination with loss of profit exposure.

- If you disagree with a DAAB decision or a 3.7 determination, the answer is to challenge it through Clause 21 – not to ignore it and hope it goes away.

Optional termination after Exceptional Events – Clause 18.5 & 18.6

The “disaster switch” in FIDIC: when prolonged war, sanctions, catastrophes or legal changes block the project, Clause 18.5 / 18.6 (and 19.6 / 19.7 in 1999) let both Parties shut down the Contract fairly on a cost-based basis.

“Substantially all” Works prevented for 84 days continuously or >140 days in total by the same Exceptional Event / Force Majeure.

Neither Party is “the bad guy”. The Contract switches into cost-based close-down mode rather than a blame game.

Contractor is paid for work done, ordered Plant & Materials, reasonable commitments, demobilisation & repatriation – but no explicit profit on unperformed work in 18.5 / 19.6.

What are we actually terminating for?

Here we leave the “your fault / my fault” world of Clause 15 and 16, and step into the no-fault exit door FIDIC gives both Parties for major external shocks:

- war, civil unrest, embargoes, sanctions;

- serious natural catastrophes; or

- changes in law that make performance impossible or illegal.

In 📘 1999 this sits under Clause 19 Force Majeure. In 📒 2017 FIDIC re-brands it as Clause 18 Exceptional Events, to avoid local-law baggage around the phrase “force majeure”.

The core test is similar in both editions:

- The event is outside the control of both Parties.

- It could not reasonably have been prevented or fully anticipated.

- It prevents performance of some obligations – it is more than just “this got harder or more expensive”.

Day-to-day, 18.1–18.4 / 19.1–19.5 deal with notice, mitigation, and EOT/Cost claims. 18.5 / 19.6 and 18.6 / 19.7 only appear when the impact becomes extreme and long-lasting.

18.5 / 19.6 – the 84 / 140-day “this project is frozen” test

Both editions use almost the same trigger. Optional termination becomes available when:

- Execution of substantially all of the Works in progress is prevented,

- by the notified Exceptional Event / Force Majeure,

- for a continuous period of at least 84 days, or

- for multiple periods totalling more than 140 days,

- and all those periods relate to the same event, not a cocktail of unrelated issues.

In 2017 the Event must have been notified under 18.2; in 1999 under 19.2.

Once that test is met, either Party may choose to terminate under 18.5 / 19.6. It is optional, not automatic: FIDIC expects Parties to ride out “normal” force majeure with EOT/Cost; termination is reserved for the point where the job has effectively become a non-project.

What actually happens when 18.5 / 19.6 are used?

Once a Party decides, “Enough – this has stopped being a temporary delay”, the sequence is simple:

-

Notice of termination

A clear written Notice is sent, expressly referring to Sub-Clause 18.5 (2017) or 19.6 (1999). -

Timing

Termination takes effect 7 days after the other Party receives that Notice. -

Mode switch

From that date, the Contract flips from “execute the Works” mode into “close-down and valuation” mode.

On the ground, the Contractor’s duties are channelled through Sub-Clause 16.3 [Contractor’s Obligations After Termination] in both Books:

- Stop all further work except what is essential for safety and protection.

- Hand over design documents and Works/Plant already paid for.

- Remove remaining Equipment and Temporary Works, and

- Repatriate staff and labour engaged solely on this project.

The tone is very different from a default termination: this is not about punishment. It is about closing down a project that external reality has killed.

How is the Contractor paid after 18.5 / 19.6 termination?

In both 📒 2017 18.5 and 📘 1999 19.6, the valuation of “what the Contractor gets” follows a very similar five-bucket structure:

-

Work properly executed

All Works carried out and measurable under the Contract (BoQ items, lump sums, schedules, etc.). -

Plant & Materials ordered for the Works

Reasonably ordered for the project; once paid, they pass to the Employer’s property and risk. -

Other reasonable Cost / liabilities

Costs reasonably incurred in expectation of completing the Works: design, long-lead orders, non-recoverable third-party commitments, etc. -

Removal of Temporary Works and Equipment

Dismantling and transport off Site or back to base (or another destination if not more expensive). -

Repatriation of staff and labour

For personnel engaged wholly on the project at the date of termination.

In 1999 the Engineer determines and certifies this under 19.6. In 2017, the Engineer uses 3.7 [Agreement or Determination], with the Contractor’s 18.5 particulars starting the 3.7.3 time clock.

Notice what is not explicitly included: loss of profit on the unexecuted portion of the Works. These are cost-plus close-down rules, not damages provisions.

18.6 / 19.7 – Release from performance under the law

If 18.5 / 19.6 are about “too much delay”, 18.6 / 19.7 deal with a slightly different creature: a legal or factual change that makes further performance impossible or unlawful, or that gives the Parties a right under the governing law to be released from performance.

📒 2017 – Sub-Clause 18.6 (paraphrased):

-

If an event outside the Parties’ control (which may or may not be an Exceptional Event):

- makes it impossible or unlawful for one or both Parties to perform, or

- under governing law entitles them to be released from performance,

- and the Parties cannot agree on how to amend the Contract to deal with it, then:

- Both Parties are discharged from further performance going forward.

- Rights in relation to past breaches are preserved.

- The Employer must pay the Contractor as if the Contract had terminated under 18.5.

📘 1999 – Sub-Clause 19.7 does essentially the same job, referring back to 19.6 for the money calculation.

So 18.6 / 19.7 are the “the law itself has killed this project” provisions, reusing the same cost-based settlement logic as optional termination.

How is Exceptional Event termination different?

All three big termination families can end up with demobilisation, valuation and payment – but the logic behind each is very different:

| Scenario | Cause / Fault? | Clause path (YB 2017) | Typical money logic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employer termination for Contractor default | Contractor breach – Contractor at fault. | 15.1–15.4 (and 15.2 in 1999) | Employer recovers extra completion costs and delay damages. Contractor may end up net paying after set-off. |

| Employer termination for convenience | Employer policy/funding choice; no Contractor fault. | 15.5–15.7 (plus 19.6 in 1999) | Contractor gets work done + demobilisation and close-down. In 2017, loss of profit on unperformed portion and other losses can also be claimed. |

| Optional termination after Exceptional Event | External disaster; no Party at fault. | 18.5 / 18.6 (1999: 19.6 / 19.7) | Contractor recovers cost-based settlement for work done, committed Plant & Materials, reasonable liabilities, demobilisation, repatriation – but no explicit profit on unperformed work in the clause text. |

A neat teaching line: “Convenience termination is a policy decision; Optional termination is a disaster decision.”

How do 18.5 & 18.6 play out in real life?

Scenario A War shuts down the project for months

Civil unrest and then open conflict block access, suspend works and freeze supply chains. An Exceptional Event has been notified under 18.2 and EOT/Cost is claimed under 18.4. Once substantially all Works have been prevented for 84+ days, either Party can use 18.5 / 19.6 to terminate, demobilise under 16.3, value under the five buckets, pay and walk away. No one is “to blame” – it is a fair exit.

Scenario B Change in law makes the Works illegal

A new regulation or sanctions regime suddenly bans the technology being installed or prohibits paying the Contractor’s bank. This fits 18.6 / 19.7 more than 18.5 / 19.6: the event under governing law makes performance impossible or unlawful or entitles the Parties to be released. If no amendment can fix it, notification under 18.6 / 19.7 releases both Parties, and the Employer pays as if there had been an 18.5 / 19.6 termination.

Scenario C Force majeure vs change in law vs convenience

A government cancels a project and passes a law freezing its funding. Is this convenience, change in law, or Exceptional Event? It depends: pure policy choice → 15.5 (convenience); impossibility/unlawfulness → 18.6 / 19.7; physical prevention on Site → 18.5 / 19.6. Money outcomes differ, so Employers push towards “Exceptional Event/change in law” and Contractors push towards “convenience” where they can.

How to use 18.5 / 18.6 without getting lost

For Employers & Engineers:

- Keep a clean Exceptional Event / Force Majeure log: dates, what happened, which parts of the Works were affected.

- Regularly review: “Are we close to the 84-day / 140-day thresholds for substantially all of the Works?”

- Align 18.6 / 19.7 with any strong local-law concepts of impossibility or statutory termination in the Particular Conditions.

For Contractors:

- Treat 18.1–18.4 / 19.1–19.5 as claim engines first, termination engines second: protect EOT and Cost before thinking of exit.

- Maintain a timeline of prevention for the whole of the Works: “Which periods were we actually prevented from executing most of the job, and why?”

- Show that this is due to a single Exceptional Event, not a mix of unrelated causes.

When drafting Particular Conditions:

- Think carefully before changing the 84/140-day test – too much tinkering can break FIDIC’s risk balance.

- Clarify how insurance, bonds and parent company guarantees behave after an 18.5 / 18.6 termination: they should generally be released in step with the cost-based settlement logic.

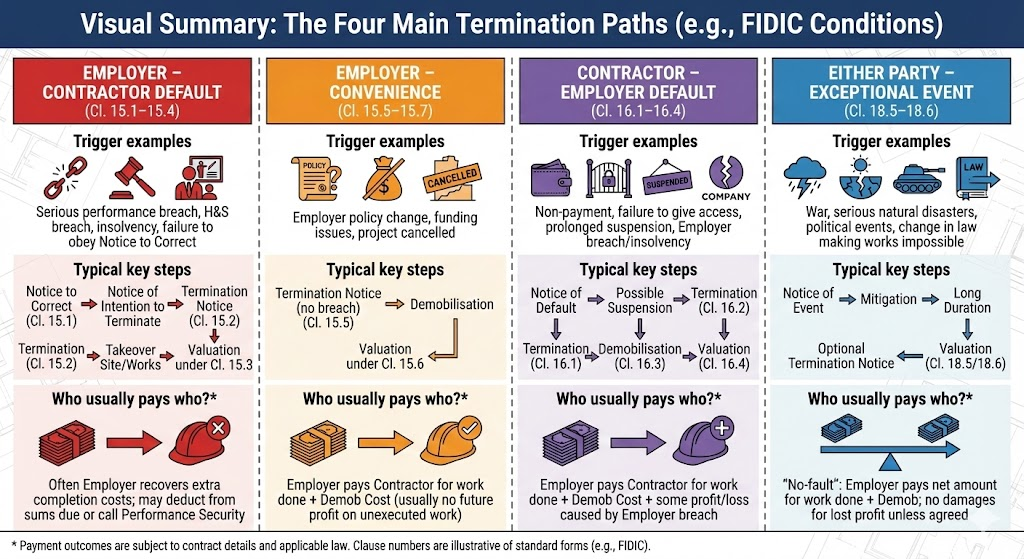

Visual summary – the four main termination paths

A one-screen map of the four FIDIC termination routes: what triggers each path, the typical steps, and – crucially – who usually ends up paying whom.

| Path | Trigger examples | Typical key steps | Who usually pays who?* |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Employer – Contractor default

(15.1–15.4) |

Serious performance breach, health & safety breach, insolvency, failure to obey a Notice to Correct, refusal to comply with binding determinations / DAAB decisions (2017). | Notice to Correct → Notice of intention / 15.2.1 grounds → Termination notice → Employer takes over Site/Works → Engineer runs valuation under Clause 15.3 and Employer’s claims under 15.4 + 20. | Employer frequently claims to recover extra completion costs, delay damages and other losses – often by deducting from sums due and/or calling the Performance Security. Contractor may end up net paying after set-off. |

|

Employer – convenience

(15.5–15.7) |

Employer policy change, funding evaporates, project cancelled or radically re-scoped without Contractor default. | Termination notice under 15.5 (no allegation of breach) → Contractor demobilises under 16.3 → Engineer values under 15.6 (2017) or 19.6 (1999) → Employer pays within the 15.7 timeframe in 2017. | Employer pays Contractor for work properly executed, Plant & Materials, reasonable close-down / demobilisation Cost – and in 2017, potentially loss of profit and other losses caused by convenience termination. |

|

Contractor – Employer default

(16.1–16.4) |

Non-payment of certified sums, failure to give access/possession, prolonged suspension of the whole Works, failure to provide financial evidence, Employer insolvency, or ignoring binding determinations / DAAB decisions. | Notice of default under 16.1 → possible suspension or slow-down → Notice of intention to terminate under 16.2 / 16.2.1 → Termination notice → Contractor demobilises under 16.3 → Valuation/payment under 16.4 + 18.5 / 19.6. | Employer must pay Contractor for work done, committed costs, demobilisation and repatriation, plus loss of profit and other loss/damage caused by Employer breach (16.4 is specifically carved out from the usual “no loss of profit” limitation in 2017). |

|

Either Party – Exceptional Event

(18.5–18.6 / 19.6–19.7) |

War, serious natural disasters, political events, sanctions or changes in law that make performance impossible or unlawful, after prolonged prevention thresholds are met (84/140 days). | Notice of event under 18.2 / 19.2 → mitigation and EOT/Cost under 18.4 / 19.4 → “Substantially all” Works prevented for 84+ days or 140+ days total → Optional termination notice under 18.5 / 19.6, or release under 18.6 / 19.7 → Valuation on a cost-based basis (5 buckets). | No-fault logic: Employer pays net amount for work done, Plant & Materials ordered for the Works, reasonable costs/liabilities, demobilisation and repatriation. There is generally no explicit damages line for lost profit on unexecuted work unless agreed in Particular Conditions or local law. |

What-if scenarios (and why administration matters)

Three short “what if…?” stories that show how a missing Notice, an over-hasty Contractor termination, or a poorly handled Exceptional Event can flip the risk profile of the whole project.

“Q. Contractor is horribly late. Can I just terminate under 15.2 without a 15.1 Notice?”

- For delays and quality issues, tribunals and DAABs usually expect a clear Notice to Correct under Sub-Clause 15.1 first, unless the wording of the Contract or local law clearly allows immediate termination.

- Skipping 15.1 can turn a “Termination for Contractor’s default” into a wrongful termination – meaning the Employer effectively becomes the defaulting Party and may owe damages instead of recovering them.

“Q. Employer hasn’t paid my IPC. Can I terminate?”

Under Sub-Clause 16.2, the Contractor’s right to terminate depends on three linked elements:

- a sum that has actually been certified,

- a clear default in payment after the final date for payment, and

- proper Notice and cure periods being observed.

If the non-payment flows from a genuine certification dispute (for example the Engineer has reduced the amount, or the Employer has a defensible set-off), the Contractor’s 16.2 termination right is much weaker.

Smart Contractors usually:

- run the non-payment as a Claim under Clause 20 in parallel,

- use 16.1 suspension first as commercial leverage, and

- keep 16.2 termination as a last, legally reviewed step – not an angry reaction.

“Q. Neither side can realistically perform; do we just walk away?”

If the event fits the Exceptional Event / Force Majeure criteria:

- Either Party may eventually terminate under Sub-Clause 18.5 (2017) or 19.6 (1999) once the prevention thresholds (84 / 140 days) are met.

- If a change in law actually prohibits the Works, Sub-Clause 18.6 / 19.7 may release both Parties from further performance, with payment calculated on an 18.5 / 19.6 style basis.

Careful sequencing matters:

- early Notices of the event and its consequences,

- evidence that substantially all of the Works were truly prevented,

- respecting the waiting periods before any termination step, and

- a clean valuation and certification process at the end.